Ethel Richardson’s 1910 novel about a free-spirited 14 year old country girl refusing to be sculpted and made to fit a mould of British Empire-influenced respectability was adapted with its most important themes and spirited sense of humour intact by Bruce Beresford in 1978. At the time the young director had just finished the seminal Don’s Party (1976) and, before that, a pair of crude Barry McKenzie vehicles starring a young Barry Humphries who would feature prominently in this, Beresford’s first attempt at a film striving to address heightened literary sensibilities.

It’s the turn of the century in rural Victoria’s Warrenega where the unfortunately named Laura Tweedle Rambotham (Susannah Fowle) is about to be shipped off to Melbourne’s prestigious Ladies College. Laura is ridiculed for her frightful red bonnet by the College’s representatives on the train journey and upon arrival finds herself immediately at odds with the school’s airs and graces. The stern and uppity Mrs. Gurley (Sheila Helpmann) assaults her with a litany of rules and regulations before she’s even had time to catch her breath. It’s a clear indicator of the kind of superior attitude that saturates these hallowed halls.

Laura has a love-hate relationship with most of the students; she’s not incapable of taking part in their irreverent, playful, girls-own activities but when it all boils down, she’s viewed as an outsider, earning gently mocking nicknames like “Tweedledum” and “Ram’s Bottom” in the process. She’s an ugly duckling pressed into the company of graceful swans, yet continues to flabbergast and then infuriate students and teachers alike with her blasé attitude and direct, unrefined manner. She shows startling aptitude for the piano as well which will cause a jealous division later on, but in a world where conformity most pleases the teachers, her eagerness comes across as impertinence; her politeness as naivety or ignorance.

Laura’s modest origins are a source of constant stress; her mother runs the local post office in Warrenega and the fact of it becomes a dirty secret she attempts to divert focus from to ease the embarrassment. To her credit she quickly develops a tough outer layer, able to turn the tables on newcomers in her second year, grilling for points of weakness with which to exploit them down the track. But she experiences guilt immediately afterwards – surely a reaction much closer to that of the true Catholic the teachers would like her to become!

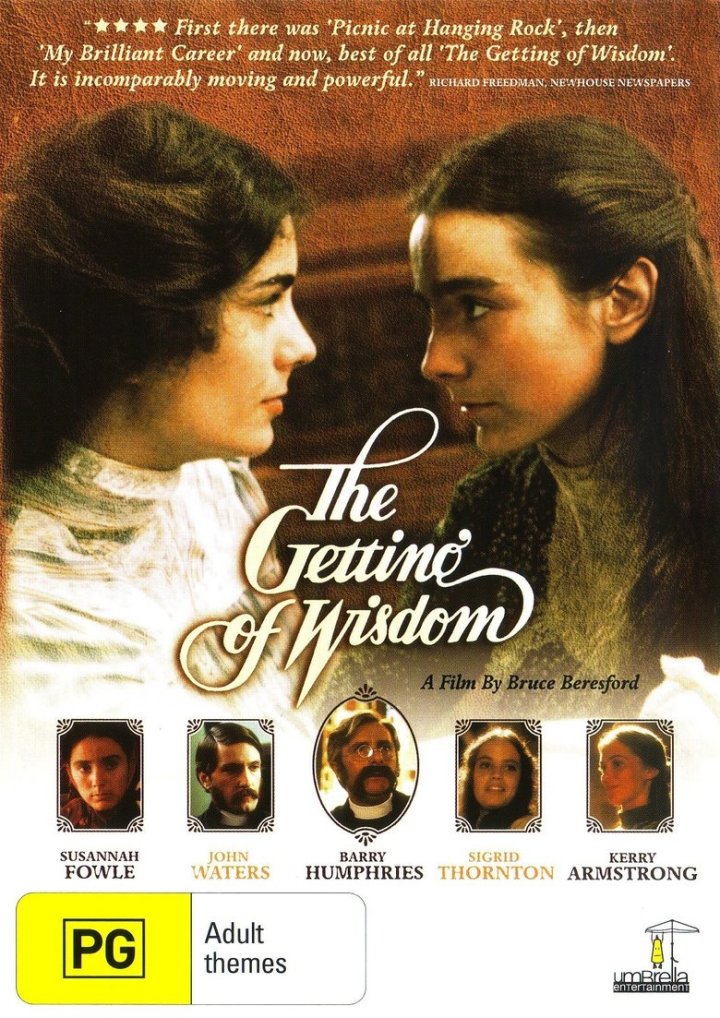

Much of the success of The Getting of Wisdom hinges on its performances and debutante Fowle was a great choice to personify the memorable Laura. She’s funny, moving and engaging with a wonderful naturalness to her performance, a lack of inhibition that immediately has us siding with Laura rather than the majority – teachers included – who often walk around as though balancing invisible books on their heads. The younger cast members are equally good; nestled amongst them are familiar names of today in early roles like Sigrid Thornton and Kerry Armstrong. The distinctive looking Kim Deacon is especially good as Laura’s roommate Lilith, whilst John Waters makes the most of his few scenes as the school’s newest recruit, Reverend Shepherd, whom all the girls are instantly and madly besotted with. An almost unrecognizable Barry Humphries offers convincing fire and brimstone moments as their principal, Reverend Strachey; his public denouncement – via a wrathful hailstorm of public accusation – of a girl caught stealing is an electrifying outburst and memorable moment.

Though not explicit, a harsh religiosity is often inferred; an adherence to purity that ultimately chokes creativity and leads to deception to escape thunderous retribution. After getting herself invited to Reverend Shepherd’s home, Laura resorts to fabrication to infuriate the other girls who’ve gone mad with jealousy and suspect a mortifyingly “sordid intrigue” between them. But it’s a fickle world, Laura discovers, for once her playful deceit is flushed out into the open, the girls are no longer playing. They converge on her like a coven of razor-tongued witches, only jealous that Laura’s time spent alone with the Reverend wasn’t theirs to brag about.

The subtle work of Hilary Ryan as Evelyn, the object of Laura’s obsession later on, can’t be underestimated either. She projects a reserved, dignified grace that snares the vulnerable Laura in her web; the younger girl is tantalised by her maturity, sophistication and ability to deal with men who Laura hates and fears in equal measure. The faint crush Laura develops for her will eventually become another painful but instructive chapter on her path to maturity and finding her true self but for a while, fed by her immature longings, Evelyn proves to be the embodiment of everything Laura aspires to become.

The final two sequences pose fascinating questions in ambiguous ways. From a first-person perspective we see Laura receiving congratulations on her successful transition to accomplished pianist. Everyone is there in fleeting glimpses, a succession of figures that dogged and chided her along the way. But are they real or just wishfully provoked faces conjured from her wildest flights of fancy, a future she’s dreamt up in self-preservation or revenge?

Finally there’s the sight of Laura taking off from the group in a park setting; just off to “have a good run” she tells them. She disappears through the ranks of park revelers – the jaunty brass band, the elegant ladies escorted under sun umbrellas – to a point on the distant horizon. But is she just running away, or towards something specific? Is this closing scene an affirmation of Laura’s free will? Or simply a negation of the limited possibilities of life at starchy institutions of learning like The Ladies College with their active discouragement of individuality? Either way, The Getting of Wisdom remains an Australian classic and one of our more enlightening and entertaining coming-of-age stories.